An Interview with Maddy: 5 Years of Raising Young Kids and Navigating Her Dad's Cancer Treatment

On giving birth at the same time as her dad received a cancer diagnosis, supporting him long-distance (during COVID), and the things that helped her heal and feel loved along the way.

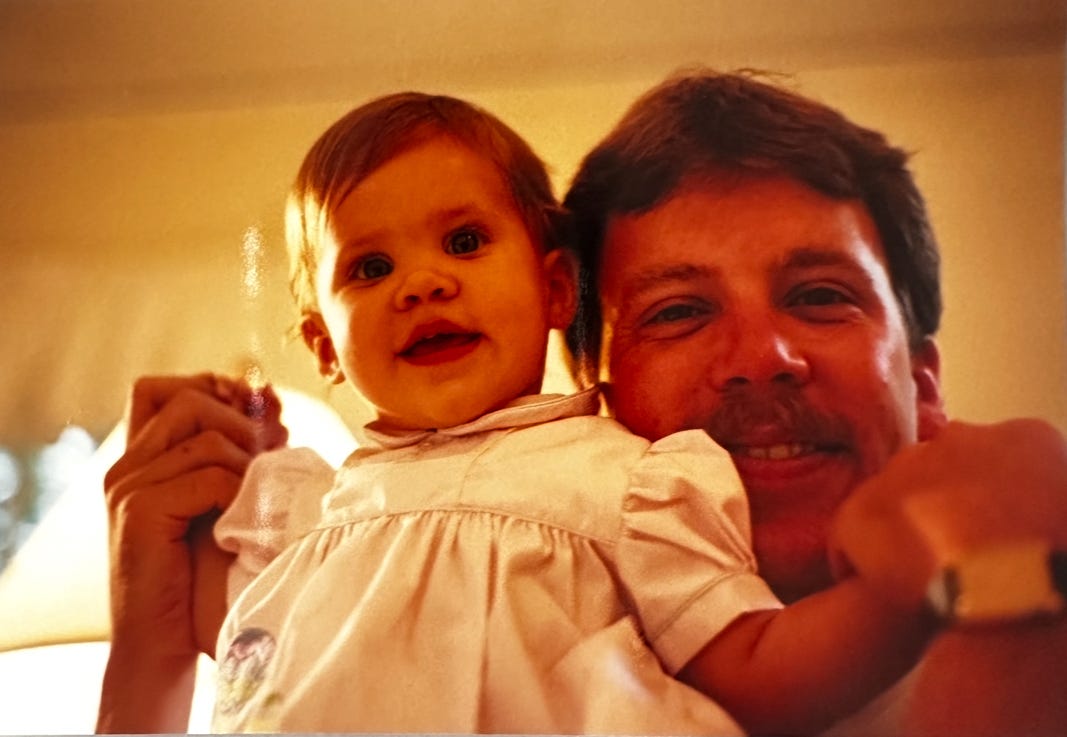

Maddy’s journey in the Sandwich Generation begins when she gave birth to her first son at the same time that her dad, Brad, got diagnosed with stage 4 kidney cancer. She shares the heaviness of translating complex medical information for her family, the challenges of balancing caregiving with new motherhood during the peak of COVID, and the profound way that parenting our children helps us experience our own grief and sadness.

A Diagnosis and the Start of a Parallel Journey

Lissy: So can you start by just sharing about your family? Your kids, your siblings.

Maddy: I’m married to Shane. We have 2 kids, who are almost 6 and almost 3 years old. We have two dogs. I grew up with two sisters, and I’m the middle sister. My older sister lives in England and my younger sister lives in Bend, Oregon, which is also where I live. My mom lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. My father, Brad, passed away in March of this year.

Lissy: Can you share about when Brad was first diagnosed?

Maddy: So, my parents were here in Bend, because I was due to give birth to my first son. We ended up being in the hospital at the same time. My dad thought he had a UTI, he was just having some health stuff, and so they went to urgent care. Urgent care said you need to go to the hospital. And I was in labor and had no idea he was 2 floors up being told he had cancer. It was a very strange life cycle moment. This is January 2020.

At the time, he didn’t tell us anything, no one knew. He didn’t want to ruin the whole new baby moment. At the time, when I didn’t know yet, I was pissed because he wasn’t being very lovey toward his first grandchild, and he’s a very lovey guy. And so I was like, what the hell, Dad? Act like you are happy about this. And I had some guilt around this afterwards, once he told us.

So they go home, see the doctor, and he was diagnosed with stage 4 kidney cancer. It had already moved from his kidneys to some lymph nodes and glands, and he was scheduled for a surgery. This is also when COVID started. So while getting diagnosed at stage 4 sucks, if he would have been diagnosed a couple months later, his surgery probably would have been pushed off, and he probably would have died within the year. The timing is crappy, but also kind of amazing. So he had surgery to remove everything that was affected. We hoped that would be the end of it, and unfortunately it wasn’t.

If you looked up the stats with when he was diagnosed, it says 5 years is the longest you can live. And, you know, you always just hope that that’s wrong. He made it 5 years and 2 months. If you’re being pragmatic about it, it all went the way that they told us it would.

A Perpetual State of Uncertainty

Maddy: With his treatment, it was never: go do a round of chemo, be done, do a scan, see if there’s anything. He was constantly on something. He went in for infusions for Immunotherapy, and his chemo was a pill. He did a cocktail of various things, and it was always like, okay, try this, and then the scan showed this isn’t working so we’re gonna try something else.

But yeah, we always knew he wasn’t gonna be a bell ringer, where the cancer’s gone. And we knew that it would be what he died from, we just hoped it would be when he was 80, not 70. And you know, he never lost his hair, he never lost his appetite, he wasn’t miserable after treatment, so it wasn’t staring you in the face that he had cancer the whole time.

Lissy: Yeah. But also, you never got that moment of ringing the bell, and having a moment to exhale, even temporarily.

Maddy: No, it was constantly, Oh, that scan was not awesome, but it wasn’t horrible. And unfortunately, he had a rare cancer, on top of just having cancer. It was rare, so there weren’t many stats. I’m kind of an information person, so I wanted to be able to read studies on the treatments, and there just wasn’t much. It was all experimental from day one, so that was hard for us to wrap our heads around, because we couldn’t see a runway. I mean, even at the end, the last week he was alive, we were like is he dying? Is this it? And they were like, yeah, it might be, but he could also turn around, so... It was kind of a mindfuck, for lack of a better word, the entire time.

Lissy: Right. I think when the information is clear, you can do some emotional processing to help yourself through what’s happening, but then when there is so little information, you’re in this perpetual state of not wanting to give up on your dad, but also wondering what the fuck is happening right now. And how are you supposed to know how to orient yourself within this information?

Maddy: Right, yeah. My mom has struggled with that a bit, because she’s like, why didn’t I just quit my job and we could have traveled knowing we only had 5 years left, you know, or do something like that. But it’s like, by saying that, you’re also saying you only have 5 years left, and you’re in this mindset of death at all times, and that’s not a way to live either, in my opinion.

I think we all struggled with that since he passed. Did we do enough? You know, COVID was raging for the first 2-3 years that he had this, and so we didn’t visit as much, because we had a newborn baby, and then later I was pregnant. And we just didn’t know enough about COVID. And he was immunocompromised from his treatment, so we had to do the 10-day quarantine and all that. We feel robbed of time on that end, we feel robbed of time on this end, and at the end of the day, it’s never enough time, I guess.

Lissy: You do the best you can with the information you have at the time, and I think with where we are at now with COVID, and how the landscape has shifted, and I think it can be hard to remember and stay grounded in how chaotic and urgent and terrible it felt at the time.

Maddy: Yeah, and like you said, we’re making all these decisions with the information in front of us. We weren’t looking back, knowing what we know now. But it’s hard to remind yourself of that.

Stepping into the Caregiver Role

Lissy: What was your role during his treatment? And was this a role that was familiar to you in other ways?

Maddy: Yeah. We’re lucky that my mom is a nurse and understood 90% of what they were telling her, for normal pre-cancer stuff. She always understood what was happening, with her parents, or my dad’s parents. It was interesting to see how she kind of lost that when she was sitting next to my dad. I’m not blaming her in any way, but you could tell it was overwhelming.

Lissy: I think for your mom, she was sitting there as his wife. And then they’re speaking to her as a fellow medical professional, and it’s really hard to absorb that when you’re holding these two roles.

Maddy: Yeah. It was probably very hard for her, yeah. We don’t live in Wisconsin, so we couldn’t be at every appointment, but I stepped in where I could to take the information about the next treatment, look stuff up, and then I would send emails to the whole family of what I view as layman’s terms, because it’s very confusing. And I did that for the scans, too. I would read all the information in his MyChart, highlight what made sense, send everyone little bullet points.

You have to advocate for yourself a lot in the health space, and if you don’t have someone who knows how to read that stuff or understand the research jargon, it can be very intimidating. So that was my role a lot of the time. It was an expected role because of my professional background. But sometimes it would have been nice to just be the one being like, yeah, sure, sounds good.

Lissy: To get to just show up and be the daughter.

Maddy: Yeah, and I think what’s hard about it is I didn’t want to be in charge of the decisions, you know? I wanted my dad to feel like he could be. But he didn’t understand them, and so it was a hard place to be, because I guess I was helping determine the treatment plan. And my sisters are making this decision based on what I told them, so it felt a little heavy at times, and like you said, sometimes I just wanted to show up and be the daughter who didn’t need to do that.

Positivity, Frustration, and Unfinished Business

Lissy: I’m curious about what your conversations with your dad were like. Were you talking about how he was feeling as he was going through treatment, both physically and emotionally?

Maddy: Yeah, we talked quite a bit about it. He’s an emotional guy when it comes to spreading the love, right? Brad loved everyone, loved being the center of attention, that kind of stuff. But we realized in the end, more toward the end times, that he might have been protecting us a little bit from how he was feeling.

His biggest side effect was GI stuff, but then it could be made better by eating healthy, which is something he never did. And so he’d have 2 hot dogs and 4 beers, and then feel like shit, and we’re like, uh-huh! So, our conversations, unfortunately, were often us feeling frustrated that he still wanted to have his cocktail, and he still wanted to have his big burger, and it was frustrating, because you’re like yes, it’s your choice, but, what is the impact of doing that. And I think his mindset was, if I’m gonna enjoy my time, I want to enjoy it my way. And you know, you have to respect that, right? It’s his life, it’s his choice.

Emotionally, I think that once in a while, he’d get really down. Usually it was after a scan that was not promising. On the eve of a scan, he was always like maybe this’ll be the one where they see nothing. And that was hard, because I knew that wasn’t going to happen, but he always was hopeful. Overall, it was amazing how positive he was through all of it. But understandably, he had low points, for sure.

Maddy: Our family’s really open with one another, probably too open, and maybe a lack of boundaries, for sure. But because of that, we talked a lot about how he was feeling. Especially in the end, in the last couple of visits home, we each took time with him. We were trying to say you’ve been such a wonderful father, make sure he knew.

And his big thing was, who’s gonna take care of who? Like, assigning roles, you know? He’s like, you need to be in charge of this, and make sure so-and-so’s okay, and you know, help mom with these things, and we’re like, yeah, this isn’t the moment for that. You don’t need to list out your responsibilities and make sure that hat’s put on someone, you know? So I think that was just more him, probably struggling emotionally at the end.

Lissy: Yeah, and to me, that so speaks to him wanting to get verbal confirmation that you guys will be okay.

Maddy: Yeah. He definitely wanted us to just be like, we’re gonna be fine without you, but that’s not how it felt, you know? There’s no way to have that conversation. It’s not Hollywood, it’s not going to be this beautiful closure. It’s always going to just be shitty.

There’s certain things we all still wish we could have said or shared, and there are things that we didn’t get from him that are frustrating too. My sister’s not been married yet. And she and my dad have always been the closest, similar processing and how they think, they’re very similar. And I was, in that moment, thinking ahead to if she does get married, or those big moments that she won’t have him there for. I asked if he could just write a little letter, something I can give her. And he was pretty weak at the end, so maybe send me a voice note, send me a text, something I can give her. And he didn’t do it, he never did it. And that pisses me off, it pisses her off. And then, you kind of find yourself saying why am I mad at my dead dad? He’s dead. Don’t be mad, that’s not fair. But the emotion’s still there, you know?

Lissy: Yeah. I think it’s okay to feel mad about the things that you wish could have been different, you know? I think so often it’s like, oh, I can’t be mad at him, he’s gone, but that emotion speaks to the continuing relationship that you have with somebody after they die, where you can still feel those emotions about things, because it’s part of missing them, because you wish they had done that, you know, and I think it’s like important to let yourself have those moments when they show up.

Maddy: Yeah, I think it reminded me of the feelings of, as you become an adult yourself, realizing that your parents were parents for the first time. Also, that they’re humans, that they have faults, that they’re not these, perfect pedestal people. You see them as these humans for the first time. And it’s hard, because you’re like, no, you’re supposed to have all the answers, and have made all the right decisions, and I’m supposed to just be able to follow along like a little duckling. And so it’s kind of the same feeling, where I don’t want to be mad at him, because it was his life and his decisions. It’s a weird amalgamation of all these emotions at once, and trying to tell yourself it’s okay to feel all of them, when some of them, honestly, just feel like you shouldn’t.

Lissy: Yeah, totally. And I think to your point about realizing your parent is parenting for the first time, it’s also that you are going through this as a family for the first time, having somebody get sick and die within your family. There’s no path that you can follow, you’re figuring it out as you go, and it’s super messy, and there are always going to be the things where you’re like, oh, we really fucked that one up, you know?

Maddy: It’s interesting, there are some moments that I think we’re all disappointed in how we handled it, or what we did, or whatever. Just not going home more, you know, stuff like that. And then there’s other things where I’m so proud of all of us in different ways. It’s very confusing.

Timelines and Mindsets

Lissy: I’m curious, are there things from your experience supporting Brad that you will carry with you into how you manage future situations you find yourself in? Or things that you will definitely want to do differently?

Maddy: Definitely. One of my first thoughts, and again, something I had guilt thinking about this, but one of my thoughts after he died was, oh my god, we have to do this 3 more times, because it was so heartbreaking, and it was so heavy. And you start thinking about everyone else you love, and it’s too much, you know?

There are things, especially with the boys, trying to guide them through it was hard. Trying to help them go through it in a way that felt healthy, but also not shielding them from it, because you can’t. And so there was a lot that I think I learned, certain ways to talk about it with kids.

And there are definitely things I would do differently with the other parents. If any of them get cancer, I will take the timeline more seriously. Not that we were ignoring it, but we definitely were just like, he’s gonna be fine, you know? Because that’s how you protect yourself, because you can’t live for 5 years thinking oh, my dad’s dying. That’s exhausting.

But I do think being more realistic with each other, maybe not with the person who is sick, because I think sometimes that’s not fair to put that burden on the person, and they might not want to talk about it in that way. You know, the patient themselves, I think it’s their choice, but I do think everyone else should talk about it more, because we were trying to just rally around his positivity. And I think maybe being more realistic about it, maybe we would have done nothing different, but it feels like we would have been more intentional about time spent together.

So yes, there’s always going to be things we would have done differently, but I think just taking more seriously any real timeline. And then there’s the financial stuff, oh my gosh. I learned a lot about finances and the business of death. It’s so annoying. It’s like, this person died, you’re in your worst state ever. And the funeral director is like, okay, here’s the packages, which one do you want? My parents planned to a certain extent, but they didn’t plan everything that could have made those moments easier. My mom has gone absolutely bonkers since then on estate planning. Her shit is tight now, because she’s like, I am not making you guys do that for me.

Processing Through Parenting, Books, and the Support of Loved Ones

Lissy: While Brad was sick and then after he died, what were other things that you found to be really helpful to you?

Maddy: Yeah, I’m a stories person, and so I read a lot of books. Not self-help vibe, but books that had characters who experienced death or were going through it. That was helpful to me, to escape, but also acknowledge what I was going through.

Lissy: Do you remember any of them?

Maddy: Yeah, Lost and Found by Kathryn Schulz.

Lissy: I fucking love that book.

Maddy: Yeah, she’s a phenomenal writer. It’s about her falling in love and her dad dying, it’s her best part of her life and the worst part of her life all happening at once. It’s an amazing book.

And I feel like I’m talking about the kids a lot, but that’s the phase of life I’m in. Helping my kids through it made me talk to myself nicer about it, you know? They would cry or randomly be like, I miss Bop Bop, and I would say to them, it’s okay to miss him, and we can talk about him. Even just saying out loud when I was feeling it, you know? Showing my kids that was okay made me understand a little bit better that it was okay. I think that helped a lot.

And after Brad died, my older son asked some pretty deep questions about death, which was scary, as a parent. You don’t want to mess up in that moment. You know, it’s like when kids ask questions about sex or childbirth or whatever, you’re like, this is my moment, I gotta get it right, or they’re gonna forever be like, do you remember when I was 6 and you told me that fucked up thing?

And the Child Life Specialist at the hospital was wonderful. She came in with Magnatiles and dinosaurs, and then also encouraged things like drawing this picture of you and your grandpa, making it about what was happening, too. And she gave them these bears, they each got a bear, and my dad had one. And the whole idea was that when you hug yours, he feels it in the hospital after we leave. And so then when we not there, my mom would send photos of him with the bear. The Child Life Specialist kind of gave us permission to be really open with them about it, because I think I was so nervous about them not understanding, or it being scary, because, you know, hospitals are really intimidating and scary, and some of the stuff he had going on was maybe scary to a kid.

I think one thing we were good at is that, you know, at the end he looked sick. He had tubes and drains and all this equipment, and we still put the boys on the bed next to him and let them touch him and hug him. It wasn’t this big, scary thing. We’re gonna kiss him, we’re gonna love on him, and we’re gonna let the boys do the same.

I have a very supportive relationship with my husband and my friends, so I felt very supported. I had one friend who would just text every morning and say, I love you, today’s a new day, little things like that were so lovely. And you and Kayla coming to Wisconsin, I still could burst into tears about that. You guys just were there. You didn’t need me to be anywhere, you didn’t show up unannounced, you just were there if I needed anything. So those are the things that stick out to me when I think back on what I needed and what was provided.

I didn’t feel unsupported in any way. So, I think in terms of what would I have needed? Just more space to be allowed to just be a daughter who is sad, you know?

The Final Moments

Maddy: Shane and I didn’t want our kids there when my dad died. I didn’t think that they needed to be there, and I also wanted to be there, fully. Kids have shit timing. My son is screaming at me that he has to poop or wants a snack, and my dad’s taking his last breaths? No thank you.

Lissy: Yeah, I think it speaks to being able to control the things you can control to be able to just show up as a daughter in that moment. You can be a parent in all these other moments, and all these other ways that you’ve navigated how to support him in this. But you needed to just be able to show up and be there for your dad as his daughter and have this experience. I think that makes so much sense.

Maddy: Yeah, I mean, there were people in and out of the house all day, and so you’re in this weird situation with being a hostess, grieving, small talk. My dad loved his people, and he wanted them there, and he kept saying, tell my friends to come by, and this and that. He deteriorated pretty quickly throughout the day, so then he couldn’t talk as much, but when his friends were leaving, he gave them this wave. He hadn’t really moved for a while, and so he gave them this wave that they now cherish, and I’m so happy that they got that, because it was such a nice goodbye for his best friend.

My parents watch Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy almost every night, we did it growing up, it’s just a thing we do. And after everyone left, and we turned on Jeopardy, because we were not just gonna sit there and watch him breathe. We all grabbed a beer, and we had literally just cracked open our beers, and Jeopardy was playing, and I look over at my dad, and I was like, Mom, I think his breathing’s slowing down. And we were just laughing, because it’s like he waited till it was Jeopardy-and-a-beer time, to be like alright, they’re fine. It ended up being really beautiful.

TL;DR: Biggest Takeaways and Reflections for Caregivers

Roles and their limitations: If you spend time advocating for your parent, make sure you also create space to get to show up as their son or daughter.

Grief encompasses countless emotions: It is normal to experience moments of anger and frustration towards your parent after they die, in addition to feelings of sadness and longing. Explore how you can tend to your emotional experience with the support of friends, family, a support groupo, or a therapist.

Explore available resources: A Child Life Specialist can be an invaluable resource while your parent is in the hospital. Lost & Found is a memoir that Maddy recommends to help process grief.

Timelines are personal: You may hold a different perspective than your parent on how to conceptualize a timeline or prognosis, if one is given. Respect your parent’s feelings on their timeline, and do your own internal processing in a way that feels right for you.

Life is full of firsts: When you are supporting a parent through their illness and end of life, give yourself grace and patience. You are all just people going through life’s new experiences, and illness and death is one of those experiences. You are doing your best.

Subscribe to Stress & Love for heart-forward conversations with a social worker and people in the sandwich generation - Exploring the interplay of identity, relationships, and family dynamics. Come for advice, stay for community.

Know someone who might resonate with this interview? Give them the virtual hug of sharing this interview.

Are you interested in being interviewed for Stress & Love? I’m looking to interview individuals who have gone through the sandwich generation, as well as those who are in it as we speak. To clarify: you don’t need to be a primary caregiver to be considered part of the sandwich generation. If you are supporting your parent emotionally, logistically, financially, or otherwise, and you are also navigating raising your own kids, then I would love to hear from you!

And lastly, if you are interested in 1:1 coaching and resources, please reach out to me through my coaching website, Sandwich Support Co, at the link below.

Maddys honesty about the guilt and frustration is so important. The tension between wanting to be just a daughter while also having to step into this caregving role really resonates. That perpetul uncertainty with the rare cancer sounds absolutely exhausting, and the grace she gave herself to feel all those messy emotions is something more people need to hear.